ANY DAY NOW, two 100-plus-year-old downtown Portland buildings could see demolition crews show up to tear them down, thanks to a loophole in city code.

There’s the 109-year-old Hotel Albion, which sits on the corner of SW 3rd and Salmon and houses the Lotus Café. The bar’s long been a popular hangout for city staff—so much so that Mayor Charlie Hales recalls sketching street plans for the burgeoning South Waterfront on a napkin at the Lotus during his stint as transportation commissioner.

On the same block sits the 123-year-old Ancient Order of United Workmen Temple, a majestic but crumbling brick and stone building embellished with columns and carved medallions. It was designed by Justus Krumbein, a prominent Portland architect who also designed the second state capitol in Salem.

The buildings are a bit neglected, but rich with Portland history. If the property owners have their say, though, that history will disappear via wrecking ball to make way for two shiny new glass and steel buildings.

One local nonprofit, aided by a Portland attorney who also serves on Portland’s Historic Landmarks Commission, is working to halt that process. Restore Oregon is hoping to close a code provision it says makes it too easy to remove old buildings, like the Albion and Workmen Temple, from the city’s Historic Resource Inventory.

Oregon statute requires that before a building designated as historic can be demolished, the owner must wait 120 days while the public is notified and allowed to offer alternatives to demolition. If a building is first removed from the city’s Historic Resource Inventory, though, the 120-day demolition delay no longer applies and the owner can tear it down at will. (The owner of the two buildings is identified in county records as a Eugene man named Allen Cohen, who told the Mercury he’s in the process of selling the properties. He wouldn’t say to whom.)

The loophole the buildings’ owners are trying to jump through to avoid delay was created in 2002, when Portland adopted a bit of code that allows owners to remove their building from the city’s list of historic properties merely by submitting a written request to the Portland Bureau of Development Services, which must make a prompt decision on the matter. If the bureau agrees, the once-historic building can be turned to rubble.

“This provision allows owners of Historic Resource Inventory properties to be removed on the same day their owners request removal,” says Brandon Spencer-Hartle, senior field programs manager at Restore Oregon. “On November 5, two properties that you can see from the front door of city hall were removed from the Historic Resource Inventory list with the expectation they’ll be demolished.”

Spencer-Hartle is talking about Hotel Albion and the Workmen Temple, which he’s been working hard to save.

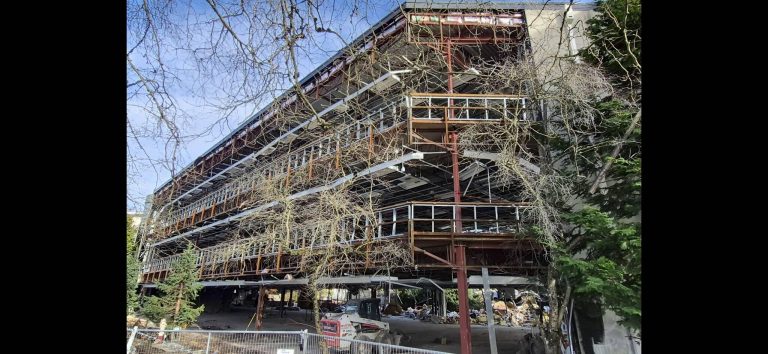

The mixed use development at 930 SW 3rd Ave, which originally proposed to incorporate the Ancient Order of United Workmen Temple NextPortland

Restore Oregon has asked the city to remove the problematic bit of code—an idea which city commissioners seem to be considering—but says that removal probably couldn’t be applied retroactively to properties already slated for demolition.

Still, Hotel Albion and the Workmen Temple may avoid the wrecking ball.

On November 4, the firm Ankrom Moisan Architects submitted a request for design advice to the city for the property where Hotel Albion and the Workmen Temple stand. The request included plans to replace the old buildings with a hotel and an office building. The development would wrap around another property on the block—the Auditorium Building—which is protected by the federal National Register of Historic Places and isn’t included in the plans. Ankrom Moisan didn’t respond to requests for comment about its plans.

The preservationists at Restore Oregon have tapped Carrie Richter, a Portland land use attorney, to appeal the city’s decision to remove the buildings’ historic designation and save them from demolition.

“City staff knew the intent was to demolish the buildings,” Richter testified about the proposed demolition at a November 18 city council hearing. “That is a real problem that necessitates amending the code and being more rigorous when these applications come in.”

Richter argues the buildings should’ve gotten the 120-day waiting period before being scotched from the city’s historic buildings list. The day after her council testimony, she made that argument in appeals filed with the city and with the Oregon Land Use Board of Appeals.

Support Mercury News Coverage

More than ever, The Mercury is relying on your contributions to help fund our news coverage. With a small recurring contribution, you can support local, independent media and help us produce more news stories like this one.

If Richter’s appeals win favor, it could give activists like Restore Oregon leverage for saving the Albion, the Workmen Temple, and hundreds of other old buildings they believe are at risk of demolition at their owners’ whim, in a city that’s been shedding old buildings lately.

“We are in the midst of a demolition epidemic… [that’s] chewing away at the character of many older Portland neighborhoods,” says Restore Oregon Executive Director Peggy Moretti. “This is now spreading to downtown. The Lotus Café building and Workmen Temple could come down without one bit of public comment or conversation…. What a loss this would be to the historic fabric of our city.”