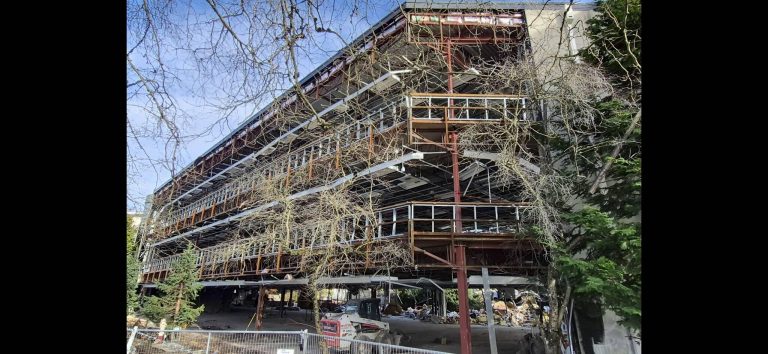

Demolition of the former Wood River Power Plant in East Alton has been progressing since this October 2020 photo was taken. Explosives will be used Monday February 1, 2021 to drop the three smoke stacks at the power station located on Illinois 143.

Demolition of the former Wood River Power Plant in East Alton has been progressing since this October 2020 photo was taken. Explosives will be used Monday February 1, 2021 to drop the three smoke stacks at the power station located on Illinois 143. Derik Holtmann dh*******@*nd.com

EAST ALTON

Some Madison County residents are concerned the demolition of three smokestacks at a defunct coal power plant will send a dangerous cloud of dust over surrounding communities. Demolition is tentatively set for Monday, said East Alton Fire Chief Timothy Quigley.

The imminent implosion caught environmental groups and residents in the region by surprise.

Prairie Rivers Network, which works on water, land and pollution issues across Illinois, first learned of the demolition a few weeks ago, said Andrew Rehn, a civil engineer with the organization. The environmental group has been following the progress since the power station’s demolition began in 2019, he added. “We thought we’d have some time to look into it,” Rehn said. “To understand the risks related to air pollution, assuming they had followed their plan and given us three months’ notice.

In a dust control plan reviewed by St. Louis Public Radio, Spirtas wrote it would notify municipal leaders, county officials and adjacent neighbors “at least three months in advance” of the smokestack implosion. The company also committed to arranging a public meeting about the demolition with municipal authorities in its plan.

Some local officials were made aware of the plan to implode the smokestacks at the Wood River Power Station last September. Quigley said his department learned of the plans then, and a representative from the Wood River Drainage and Levee district said it also was notified of the implosion at that time to ensure the levees would not be damaged.

Other elected officials were not briefed, including Robert Pollard, a Democrat who represents East Alton on the Madison County Board and whose district includes the shuttered coal power plant. The public meeting Spirtas committed to in its dust plan also didn’t happen, Rehn said. “If they’re not following that part of the plan, what other parts will be followed?” Rehn said. “On top of that, what is the plan? What does it do, how does it function, isn’t really clear.”

The main concern from residents and environmental groups comes from the lack of communication from the Wood River Power Station’s owner, St. Louis-based Commercial Liability Partners, which acquired the plant in 2019.

Representatives of Commercial Liability Partners, as well as Spirtas, could not be reached for comment.

Quigley said he’s confident that Spirtas will safely bring down the plant’s smokestacks. “This company, from what I’ve been told, is competent,” he said. “This isn’t their first [demolition]. We’re expecting everything to go well.”

Minimal communication and oversight

Toni Oplt, who chairs the Metro East Green Alliance, a small group of Madison County residents focused on environmental issues, first contacted the company when she noticed the plant had started to be demolished in 2019, following its closure three years earlier.

“We were really interested in the beginning to see if this was going to be a positive outcome to a tragic situation when the coal plant and jobs were lost and local economies really suffered,” she said.

Oplt said she wanted input from local residents included in discussions for what to do with the retired power plant. Her group sent emails, placed phone calls and submitted “contact us” forms on CLP’s website, but only got a single curt message in return, she said. “They would never meet with us, they would never talk with us,” she said. “We didn’t understand why there was no public conversation.”

State Sen. Rachelle Crowe, D-Maryville, whose district includes the shuttered power plant, requested a meeting with CLP, which was rejected, and her further requests to speak with the company were ignored, a spokesperson from her office said.

Metro East activists’ fears about the East Alton plant compounded after the implosion of smokestacks at the Crawford Coal Plant in Chicago sent a large cloud of dust over one of the city’s lower-income neighborhoods last April. Rehn and Oplt worried a similar event could happen in Madison County and contacted the Illinois EPA and other officials searching for regulations on coal power plant demolitions. “Not once could anyone ever definitively say, ‘This company will have to be accountable,’” Oplt said.

The state will roll out specific rules for coal ash ponds in March. Otherwise there are minimal regulations for how to handle old coal plants besides meeting the EPA’s asbestos standards, Rehn said. “We weren’t really able to turn up much of anything,” he said. “If there’s no process, there’s no way for the community to know what’s going to happen. There isn’t any accountability put on the company.” It’s especially concerning because nine other coal plants in Illinois will come offline or already are retired and will eventually be demolished, Rehn said. He points to what happened in Chicago as a cautionary tale. “You don’t want that happening in every single community,” Rehn said.

What’s in a smokestack?

During operation, coal-fired power plants produce many air pollutants, said Delphine Farmer, an atmospheric chemist at Colorado State University. “One of the reasons we really want to scrub any emissions from coal-fired power plants and take them offline is that they release mercury into the air, also other heavy metals, like arsenic and lead,” she said. These compounds remain in the smokestack and parts of the building after a plant is decommissioned, Farmer said. Demolition projects can create dust that goes into the atmosphere. “My larger concern with dust is that it carries things with it,” Farmer said. “Heavy metals tend to just stick onto the surface of dust really well.” Dust usually lasts in the atmosphere for a few days before falling to the ground because it’s relatively large and most of it will settle fairly close to the site of a demolition, especially if the implosion is well controlled, she said. She recommends area residents keep windows closed, have good filters in their heating systems and turn off the exchange with outdoor air in the hours after the demolition.

By Eric Schmid St. Louis Public Radio