(bid info at www.envirobidnet.com)

For most Morgantown residents, the shirt factory was always a fact of life. A surprising number of locals know, or are related to, someone who worked there. Many others bought shirts in the outlet or seconds store. George Segal, a former owner, believes there “are many doctors, lawyers, and other professionals in Morgantown who owe their educations and lofty positions in life to their mothers’ years of sewing in the Morgan Shirt Factory.”

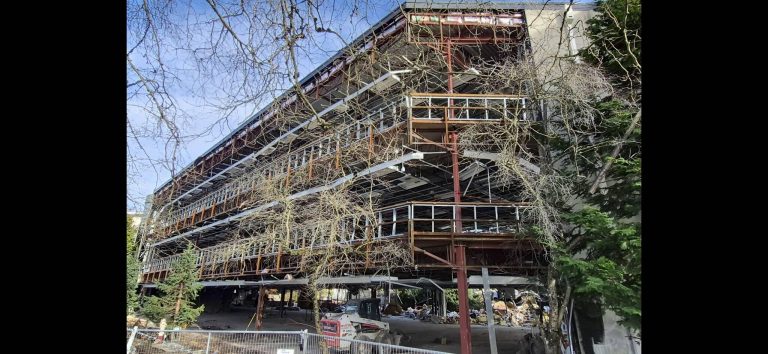

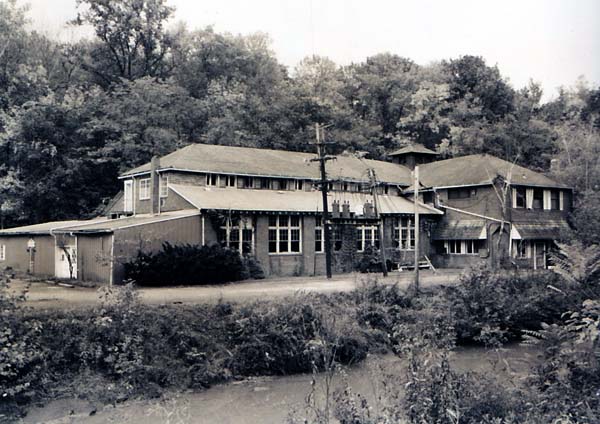

The factory building was a landmark from 1914 until it was razed in 2001 and replaced with a skateboard park. Located in the Sabraton area of town, it was nestled on the edge of Marilla Park beside Decker’s Creek, a railroad line, and state Route 7. Decker’s Creek frequently flooded the factory, causing considerable damage and work stoppages.

The industrial site was initially developed by prominent Morgantown entrepreneurs, including West Virginia University geology professor and businessman I. C. White. The Midland Manufacturing Company built the factory on a two-acre site called the Pools Rock property. The original structure was a two-story brick building with an intersecting hip-roof section topped by a hip-roof cupola. The post-and-beam construction created a large, open, interior space of approximately 33,000 square feet. The second floor resembled a clerestory, with a row of highly placed windows on the front and rear facades. This type of factory design, common nationally at the time, provided air and light for factory workers.

The new factory, purchased by South Dakota-based Midland Manufacturing on February 25, 1913, originally had nothing to do with clothing. Midland’s specialties were “bicycles, cycle cars, motorcycles, motors of all kinds, side-cars, tri-cars, motorcycle and bicycle accessories and attachments of all kinds, machinery, implements and tools.” The Sabraton factory’s initial product was intended to be Crawford motorcycles, with I. C. White as president of the board; however, the factory apparently closed without producing one cycle.

Over the next year, the site changed hands, and names, several times. In 1914, Midland sold the property to Joseph Keener, president of the Marilla Window Glass Company and an officer with Crawford Motorcycles. The deed included “all fixtures, engines, boilers, machinery, tools, appliances, patents, trademarks, contracts, books, office furniture and all materials, finished and unfinished on hand.” When the Crawford Company moved to Hagerstown, Maryland, in 1915, Keener sold the property to Walter Jones of United States Window Glass, who, in turn, sold it to the McCann-Shaw Glass Specialty Company, which changed its name to Standard Glass.

According to the 1921 Industry and Business Survey of the Morgantown District, Standard Glass manufactured “microscopic slides, bent glass, automobile glass, mirrors and beveled glass.” George Segal thinks Standard Glass made headlights and mirrors for Franklin motor cars because “workers found glass and Franklin reflectors and mirrors while cleaning out the crawl space under the factory’s boiler room after a huge flood in 1986.”

After Standard Glass went out of business in 1929, the local Commerce Club enticed Charles Greenberg to bring in his sewing equipment from New York to manufacture and sell shirts, blouses, and other apparel. By November 1934, the Greenberg Shirt Factory employed 10 men and 250 women—a 25:1 ratio at a time when many industries prohibited, or severely limited, the hiring of women. Workers were paid by piece rate (based on each piece of clothing made), and the average monthly wage was $35. Most other jobs for women at this time paid only about $13 per month.

A debate between Greenberg and the factory workers over unionization and a reduced piece rate led to a strike. On March 28, 1936, a story in the Morgantown Postread, “Workershad picketed the plant for several days and were joined by members of the United Mine Workers of America.” Greenberg responded by shutting down the plant indefinitely, idling more than 200 workers. City officials offered to mediate the dispute but were turned down by both the company and the Amalgamated Garment Workers Union of America.

Newspaper accounts noted that the company “had six months’ stock of goods on hand.” However, the finished clothing couldn’t be sold because “the company was unable to get their trucks through the picket line to get stocks from the warehouse.” After three weeks, a new piece rate was worked out, and the union was recognized to represent the workers.

Weeks later, on June 6, workers again went on strike after another pay cut. Some 200 workers walked the picket line 24 hours a day for over a month. While the workers were willing to take the latest pay cut, they wanted written assurances that the company would stay open for at least another year. Meanwhile, the city of Davis offered Greenberg a new factory and ideal labor conditions, so the company moved to Tucker County.

The factory sat empty for several months while the union and citizen groups looked for a solution. In 1937, they successfully negotiated a deal with the Raritan Shirt Company, which started producing between 14,000 and 18,000 shirts per week and then made Army uniform shirts during World War II. In 1947, Raritan added a cutting-room building, opening up space in the main factory for more production. The company was so successful that during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, it opened new factories in Woodsville, Ohio, and in Grafton, Taylor County. The union avoided any work stoppages during those decades by negotiating several three-year contracts, each of which increased piece rates and worker benefits.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the company focused more on semi-custom shirts and blouses. Among its customers were Calvin Klein, Brooks Brothers, Evan Picone, Jos. E. Banks, Gucci, Lands End, Saks Fifth Avenue, and Abercrombie & Fitch, in addition to private customers who wanted custom-designed shirts.

The Morgan Shirt Factory, as it was known by then, was the only domestic producer of the Polo Ralph Lauren line during the 1980s and early 1990s and the only known U.S. factory that could sew a variety of fabrics such as “cotton, blends, silks, rayon, wools, 10-ounce denims, 6-ounce denims, linen, and 4.5-ounce chambray with the same sewing operators.”

In 1984, George Segal, owner of Manhattan Industries, bought the business but sold it in the late 1980s, starting a downward spiral for the factory. State and local groups and private investors tried to save it through infusions of cash. New owners Harris Bass, Tommy Burns, and Bruce Krantz brought back Segal to serve as board president, believing the factory could supply better quality garments in a shorter time than overseas companies could.

Workers did their part by accepting piece rate and benefit cuts. Longtime workers, like Lula Cutlip, a 37-year employee, had borne the brunt of the company’s ups and downs. “We had it real good years ago,” said Lula. “Then things started to change. I worried myself sick about whether I’d have a job.”

Mary Soccorsi, president of the local textile union, reminisced about the times before bankruptcy and massive layoffs, “We’ve had a really bad year and a half. . . . The women in this factory are high-skilled workers. Some of them face health problems from carpal tunnel syndrome to brown lung. It’s not as bad as [factories] where they deal with the raw products, but we have to work fast and we have to work good.”

The factory had been a union plant since 1934, offering medical care, paid vacations, sick leave, and retirement benefits to workers. Many of these benefits, though, had been scaled back over time to keep the factory open.