KLAMATH, Calif. — The first of four hydroelectric dams slated for removal on the Klamath River is coming down.

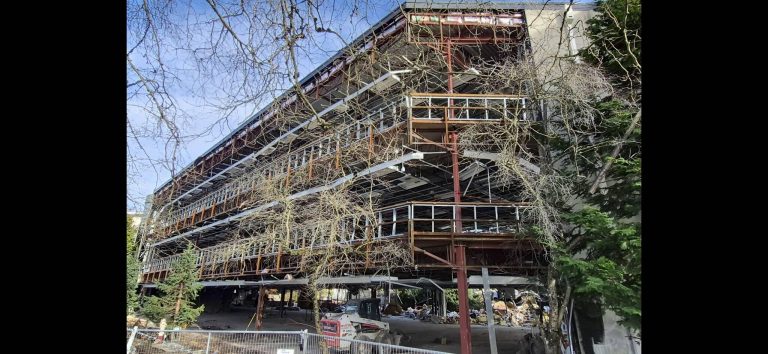

Crews recently began demolishing Copco 2 — the smallest of the four dams — officially kicking off what has been described as the largest dam removal project in U.S. history.

Copco 2 is a diversion dam about a quarter-mile downriver of the larger Copco 1, which impounds Copco Lake east of Yreka in Northern California. The name “Copco” is an acronym referring to the California Oregon Power Company which merged with what is now PacifiCorp in 1961.

Completed in 1925, Copco 2 measured 35 feet tall and 278 feet long. It diverted water released from Copco 1 into a series of tunnels and penstocks ending at a rectangular powerhouse capable of producing up to 27 megawatts of electricity.

Power generation at Copco 2 stopped June 1, and the dam is now rapidly being dismantled by heavy machinery. Final removal is expected by September.

“It certainly is a momentous occasion,” said Mark Bransom, executive director of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, or KRRC. “It is the culmination of work that has been done over the last couple of decades, most notably by tribal members and tribal governments that have been advocating for this action since the early 2000s.”

The Klamath Hydroelectric Project also includes J.C. Boyle Dam, upstream from Copco 1 in Southern Oregon near Keno, and Iron Gate Dam, downstream from Copco 2 near Hornbrook, Calif. The dams were built between 1911 and 1962, and collectively produced up to 169 megawatts of electricity.

By tearing down the dams and restoring a free-flowing river, tribes and environmental groups claim it will open 400 miles of previously blocked habitat for migratory salmon.

Razing Copco 2 marks the first step in that process, Bransom said.

In order for excavators to even reach the dam, the construction team, led by Kiewit Corp., first had to dewater the stretch of river between Copco 1 and Copco 2. That was accomplished by altering reservoir levels behind Copco 1 and Iron Gate dams.

From June 1-8, Bransom said they drew down Copco Lake by 8 feet. The water was sent downriver past Copco 2 into Iron Gate Reservoir, where it is now being stored and gradually released to meet minimum streamflows for salmon under the Endangered Species Act.

Additional storage capacity in Copco Lake has allowed for the area behind Copco 2 to remain mostly dry until the dam is fully removed.

“Of course, we have a little bit of flow. But by and large, it’s just a tiny amount,” Bransom said.

The gates, walkway and two of five bays down to the spillway have already been taken out at Copco 2. Meanwhile, hydraulic drills continue to chip away at the concrete weir, breaking it into smaller rubble pieces for disposal.

The wooden and steel penstocks that carried water to the powerhouse will also be removed in sections, Bransom said. He expects work will wrap up shortly after Labor Day.

With Copco 2 gone, Bransom said the team will then set its sights on the remaining three dams in 2024. Environmental restoration of the area, including the re-vegetation of 2,200 acres with native plants, will be ongoing in 2025 and beyond.

According to the KRRC, the entire project involves demolishing 100,000 cubic yards of concrete and 2,000 tons of steel. Total cost is estimated at $450 million, including $200 million from PacifiCorp ratepayers and $250 million from a statewide water bond approved by California voters in 2014.

Klamath dams slated for removal

California, Oregon and PacifiCorp have pledged another $45 million in contingency funds, in case the project goes over budget.

On June 26, members of the KRRC board of directors gathered near Copco 2 for a glimpse of the deconstruction. The board includes representatives from the Yurok, Karuk and Hoopa Valley tribes, which have long advocated for removing the dams to restore historically abundant salmon runs.

“It was very emotional for all of us,” Bransom said, recounting the moment. “This is the first of a number of steps that will be taken to try and restore some balance to the Klamath River, and communities that rely on the abundance of the river.”