Dozens of young people, lost in schoolwork or quiet conversation, barely looked up from their tables a few weeks ago as a knot of men and women wandered past, faces to the sunlight in the Erie Community College atrium. If the students did react, the guy they recognized was Dan Hocoy, ECC’s president. Few noticed a white-haired woman who moved casually amid the crowd hurrying to class, pausing to admire views of ECC’s courtyard and its great open space.

In no small way, those students were there because of her. Even many of their teachers were not yet born when Joan Bozer helped lead an uphill campaign to save the building, an effort seen as a pivot in the way greater Buffalo envisions both its downtown, and its future. Bozer, at 90, downplays her role. She speaks with admiration of a legion of allies, especially the late Minnie Gillette, her friend and fellow strategist, who at the time had just become the first African-American woman elected to the Erie County Legislature. “Please,” said Bozer, who served in the Legislature until 1995 and whose passion extends to many civic causes. “Don’t make it sound like it was just me.”

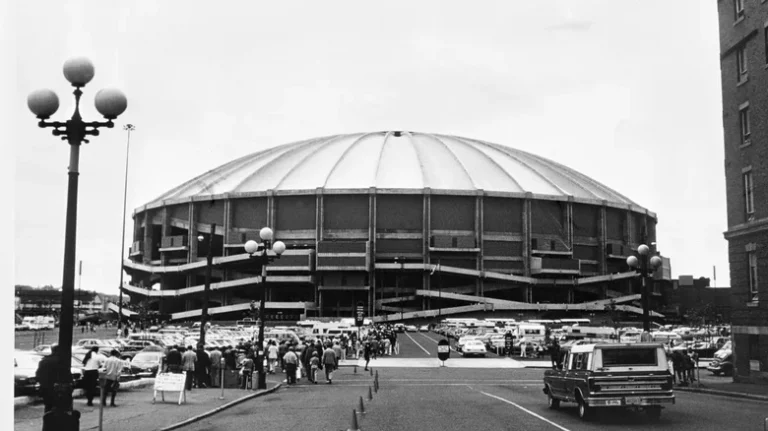

Without question, she is the central living witness. It will be 40 years next week since the Legislature took a final vote on transforming the old U.S. Post Office into a new city campus for ECC. The decision ended years of worry that a landmark of magnificent significance might end up leveled, like so many others in Buffalo. Joan Bozer, at 90: It’s been 40 years since she played a key role in saving the old U.S. Post Office downtown, now the city campus for Erie Community College. (Derek Gee/Buffalo News)

Indeed, in a 1969 letter urging Rep. Thaddeus Dulski to tear down the structure, former Erie County Democratic Chairman Peter Crotty – a politician of sweeping influence – called the post office “a mongrel structure of no authentic period, dungeon-like in its aspect, repellent to the visitor and lacking in the convenience suitable for habitation.” The building, Crotty argued, was “a monstrous pile of death-like stone.”

He was hardly alone. Plenty of people wanted the structure gone. They dreamed of opening an entire city block for the kind of 1970s development that history has shown to be, at best, forgettable.

The argument careened into the 1970s, until Bozer and Gillette – both new legislators – engineered their campaign to bring ECC’s city students into a civic landmark.

“Joan and Minnie were the frontrunners on this, and they pulled me in,” said Mary Lou Rath, a former legislator and state senator to whom Bozer gives much credit. “It was a very pivotal time. If it wasn’t restored, it was going to continue to deteriorate and eventually become a parking lot.”

Erie County Legislators Minnie Gillette, right, and Joan Bozer celebrate the start of the $13 million project to convert the old post office into ECC’s City Campus with carpenters Sandy Rotunda, left, and Jim Pagano in 1979. (Buffalo News photo)

The challenge came from its size. Architectural historian Frank Kowsky said the post office was originally approved during the administration of President Grover Cleveland, the onetime mayor of Buffalo, but did not open until 1901. The final design, a massive example of a Gothic style, was the work of James Knox Taylor, supervising architect of the U.S. Treasury.

With its hidden corners and stone eagles and granite bison heads, there is no public space quite like it in Buffalo. “It’s such a beautiful building,” said Kowsky, who compares drinking a cup of coffee in the sunlit, pillared courtyard to relaxing in Italy, in a public square.

Martin Wachadlo, a fellow architectural historian, said the building took on elevated importance in the 1970s, long after it served as the regional postal center, when its fate became a threshold moment.

If the debate had reached its apex 10 years earlier, Wachadlo said, the post office would almost certainly be gone. In the late 1960s, within a city still enraptured by demolition, Buffalo lost such jewels as the old Erie County Savings Bank and the original Statler Hotel.

“It was a traumatic effect,” Wachadlo said. He described the almost simultaneous rescue of the post office and Louis Sullivan’s Guaranty Building – an early masterpiece by the father of the American skyscraper – as turning points. “Before that,” Wachadlo said, “we had thrown so much away based on a hollow vision.”

Gillette’s focus was on a flesh-and-blood restoration. She emphasized that students from the heart of Buffalo, too often faced with massive obstacles to a college education, deserved a beautiful and easily accessible campus. As for Rath, she took a poll of her Amherst constituents, whose passionate response signaled metropolitan support.

The chief alternative was an old Bell Aircraft site on Elmwood Avenue, proposed by developer Francesco Galesi. Bozer laughs out loud in recalling the duels between the camps. One day, she said, reporters called to tell her the post office tower was cordoned off, while opponents of restoration labeled it unsafe. She insisted not only on an immediate inspection, but also on climbing the stairs herself to prove their stability. The tour included Peter Flynn, an architect from Cannon Design. Flynn recalls that while some of the stones did indeed show signs of movement, there was clearly time to save the building. But not much.

In July 1978, by a 13-7 vote, the Legislature reaffirmed a 1975 decision to convert the post office into ECC. Even that victory proved temporary. Early on a November morning, a reporter went to the door of Bozer’s Buffalo home and told her the state had scuttled a complicated financing plan. Bozer was unrattled, telling the press: “We’ll just have to go with Plan B.”

Today, that memory makes her laugh so hard she doubles over. There was no Plan B. She made it up on the spot, unwilling to give a shred of hope to her opponents. Bozer, Gillette and their allies thought fast. By early December, they embraced a new $12.5 million financing proposal in which the state Dormitory Authority would borrow the money, and the county would eventually pay back half.

On Dec. 6, 1978, the legislature approved the move by a 12-6 margin. Within two weeks, the SUNY Board of Trustees offered its support.

By 1981, Flynn and his colleagues at Cannon were finished with their work, and students were inside the grand space, taking classes. Eleven years later, when Gillette died at 62, the auditorium was named in honor of one of the building’s great champions. Today, demolition would seem unthinkable. The decision to save the post office, said Peter Flynn, was a critical break from a self-destructive mindset that physically tore Buffalo apart.”What we did until that point,” Flynn said, “was take buildings down.”

Hocoy, president of ECC, sees his college as a dramatic statement of purpose. “It does remind me of the great European cathedrals,” he said. Such landmarks were intended “to emphasize transcendence and the heavens,” he said, and to “create a sense of knowledge as upliftment.”

Last month, in an atrium where sunlight poured in like a waterfall, Bozer smiled from an overlook at dozens of students, occupied by books or screens and unaware of her presence. She praised Gillette, Rath and many allies for what they did, and offered a restrained sense of her own legacy. “I think,” she said, “this building has played a useful role.”

Dan Hocoy, ECC president: For his students, a building with the feeling of a “European cathedral.” Others are not so reticent. Forty years after the rescue of a one-of-a-kind city landmark, in a community facing constant challenges about the civic fabric, Frank Kowsky said the beauty and prominence of the “lovely Gothic spire” often makes him contemplate what almost came to dust. “We didn’t lose the post office but we came very close to losing it,” Kowsky said. “And by saving it, we really opened people’s eyes.”

Sean Kirst is a columnist with The Buffalo News. Email him at sk****@******ws.com or read more of his work in this archive.